Editor's note: This is the first in a series of DigiChina contributions by Zac Haluza, newly serving as an Associate Editor of DigiChina. Haluza's independent analysis on Chinese technology policy is published on his Root Access newsletter, formerly known as Cloudology.

Since the 20th Party Congress last October, innovation in science and technology (S&T) has become a core theme in Chinese government policy and messaging. In his report during the Congress, General Secretary Xi Jinping laid out the country’s priorities, saying S&T must remain China’s top productive force, talent must remain its top resource, and innovation must remain its top motivator. Another key message from Xi: China needs to achieve “a high level of self-reliance in science and technology.” This same messaging was repeated throughout the Two Sessions in February and March, and these sentiments have reverberated through state agencies and local governments ever since.

As an engine to drive this innovation, Xi has pointed to the importance of China’s “innovation system,” a key term in Chinese policy discourse since at least the 2006-2020 plan for S&T growth. When the CCP Central Committee and the State Council announced their state restructuring plan during the Two Sessions, it included a comprehensive reorganization of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and established the CCP Central Commission for Science and Technology, a high-level body charged with strategy and reform, as well as with the overall planning of China’s national innovation system. This bureaucratic rearrangement signals a greater emphasis and sharper focus on S&T and a new path for related industries in China.

In addition to these top-level announcements, some of the early details about what the changes to the system mean come from writings by MOST officials in prominent outlets.

A narrative of China’s science and technology history—from the bureaucracy charged with its future

On March 17, the official bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences published an article (also available here and archived here) discussing the innovation system’s history, structure, and objectives. The authors include He Defang, a MOST deputy secretary general, as well as two other ministry officials and scholars from the Shanghai Institute for Science of Science and the National Center for Science and Technology Evaluation.

SOURCE:

"Analysis and Thinking on Developing Evolution of National Innovation System 国家创新体系的发展演进分析与若干思考"

By He Defang 贺德方, Tang Fuqiang 汤富强, Chen Tao 陈涛, Luo Xianfeng 罗仙凤, and Yang Fangjuan 杨芳娟

Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences 中国科学院院刊, 2023 38(2): 241-254, doi: 10.16418/ j.issn.1000-3045.20230113002. [archived]

The article is a timely outlay of how Chinese government experts view the country’s S&T progress, the challenges it now faces in these fields, and how to best tackle them.

Early in the piece, the authors outline the development of China’s innovation system. A key aspect of this development, they write, is the evolution of the entities that drive China’s innovation—a group that now includes enterprises, research institutes, and institutions of higher education.

From the nation’s founding in 1949 until Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, they write, China had a highly centralized administrative system for S&T. Research in these fields was primarily carried out in centralized research institutes; the country’s enterprises were primarily concerned with production.

With the policies of reform and opening up beginning in the late 1970s, the nation’s industrial and S&T administrative systems experienced major transformations. However, they write, from the beginning of the reforms through the start of the 21st century, no new systems emerged for scientific research and development, as China’s patterns of scientific research still followed the drumbeat of its planned economy. Research institutes, as well as universities and colleges, were the primary entities leading the country’s research and development in S&T fields during this period, they write, but beginning in the late 1980s, China’s policy of market access in exchange for technology (which the U.S. has more recently referred to as “forced technology transfer”) brought a large number of Chinese businesses within what they characterize as a national manufacturing network.

In 2006, the authors write, these dynamics shifted to more closely resemble the landscape we know today. Specifically, China established a “fundamental, systematic framework for innovation in science and technology,” which included a diverse array of agents for innovation: research institutes, enterprises, colleges and universities, as well as new forms of organizations and alliances for research and collaboration.

Diagnosis and Prescription: Three Layers and Two Loops

Despite this progress, the authors identify persistent problems, which they say this new system intends to address:

“In comparison to the world’s S&T superpowers,[1] China’s innovation and development in S&T has no shortage of issues, such as deficiencies in foundational and critical technologies, a lack of interaction between the educational and technical industries, and a shortage of industry members in the community for S&T innovation. These issues have severely restricted the overall effectiveness of the innovation system. In the face of deep and complex changes occurring both within China and abroad, the national innovation system urgently needs to undergo a systematic transformation.”

The authors characterize this revamped innovation system as pragmatic, in which practice takes precedence over theoretical research, and “behavioral agents” such as businesses and universities form and improve their abilities to innovate through their interactions with one another. The purported key to this system’s effective operation lies within the coordinated development of two parallel systems: a “hard” system consisting of S&T ability and a “soft” system made up of laws and policies that spur innovation in science and tech:

“Thus, to effectively transform the innovation system, it is essential to maintain the cooperative evolution of technology and systems, as well as the long-term dynamic coordination between systems and goals of economic development.”

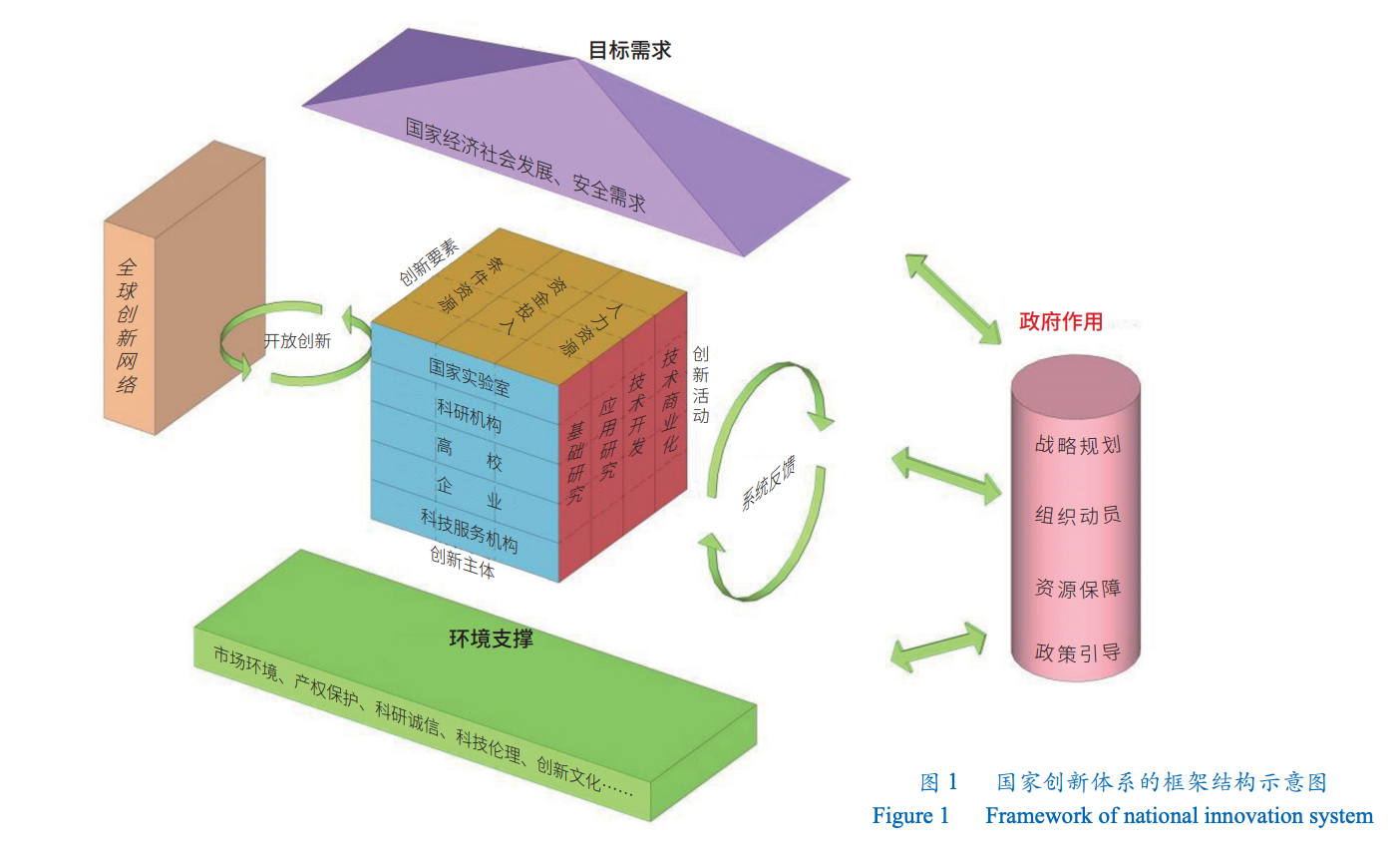

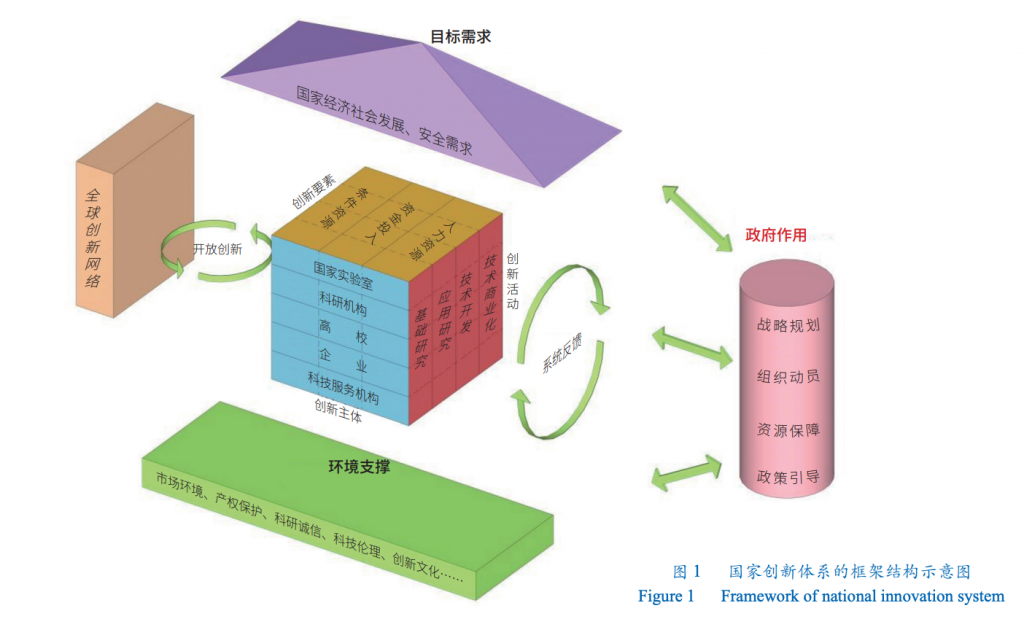

As for the structure of the new framework (diagrammed below), they write that it consists of “three layers and two loops.” The lowest and most foundational layer is that of “environmental support” (in green): market conditions, the protection of property rights, honesty in scientific research, ethics in tech, and so on. This directly supports the second layer, “agents of innovation” (the blue face of the cube), which consists of the innovation-driving institutions discussed above, such as businesses, schools, and national research labs. These agents interact with a global network of innovative entities (the peach block), constituting a “loop” of open innovation. At the same time, these agents’ contributions feed into the third and topmost layer: China’s national objectives and needs (the purple roof). Overseeing and guiding this entire flow is the government (the pink column): through measures such as strategic planning and the guaranteeing of resources, the government engages with all three layers in a “systematic feedback loop.”

A Roadmap for Central Policy Improvements

In the final part of the article, the authors share their thoughts on how China’s innovation system can be strengthened. They highlight the progress that this system has made over the last two decades, while emphasizing the challenges ahead. Bringing to mind the relationship between real technological activity and government policy illustrated above, they emphasize the need to strengthen China’s technological abilities while also improving its policy framework:

“By strengthening legislation for science and technology, creating innovative policy tools, and optimizing the environment for innovation, China can improve mechanisms, policies, and measures that are conducive to innovation, drive the iterative improvement of administration for science and technology, and make the innovation system more efficient.”

Some of their prescriptions for making China’s innovation system more effective include continuing the Party’s centralized leadership and strengthening the planning and development of education, S&T, and talent, as well as boosting enterprises’ competitiveness and innovative capabilities. For those familiar with MOST rhetoric on China’s S&T development, these solutions will certainly not come as a surprise.

Experts on the Same Page

Around the same time that the Chinese Academy of the Sciences published this article in their bulletin, they also collaborated with the state-run China Internet Information Center to interview Fan Jianping 樊建平, an expert in the fields of high-performance computing, cloud, and distributed computing who leads the Academy’s Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology.

SOURCE:

"[Hongyi] Fan Jianping: The Innovation System Should Have an Active Government and Effective Market Fulfill Their Function【闳议】樊建平:创新体系建设应发挥有为政府与有效市场的作用"

Text based on the Hongyi video program published on the Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences WeChat public channel: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/80TylLYhTm_lpjLjCNyMiQ [archived]

Fan’s comments on how China should strive to improve its current innovation system echo many of the sentiments described above:

“I believe our national innovation system should express itself in two ways: an active government and an effective market.[2] Our nationwide system is more on the government end. That which one should call an innovation system supported by government capital is currently undergoing reconstruction—from the establishment of new national laboratories to each province’s laboratories as well as the reconfiguration of key national labs, to the research and development organizations of enterprises, and even regional research organizations in different cities. I believe that these things have increased the strength of the government’s investments. Things have changed very quickly over these last few years; in this regard, [the national innovation system] should express itself through a facilitating state.

“The second matter concerns the agents of innovation, which are enterprises — in particular, innovative high-tech private enterprises. The matter is how to give play to the innovative abilities of small private enterprises; for instance, creating innovative hotspots, in the same way that Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen have become hotspots for scientific research, technological R&D, and industrialization. When it comes to the market, the aspect of finance is very important. Venture capital funds and the like must also develop. In this way, you have a facilitating state as well as an effective market; in addition, the two things will have the chance to combine with one another and also combine the advantages of China’s national system with the advantages of the market. The next steps should concern how to carry out these two things well and let them properly express themselves. China will likely move faster than the West along the path of innovation.”

Notes

[1] The term used is 科技强国, literally “S&T strong-country.” Translators and scholars debate whether to render the compound of strong and country as “power,” “great power,” “major power,” “superpower,” etc. Regardless, the reference is to comprehensively strong countries in the fields of science and technology.

[2] The terms “active government” (有为政府) and “effective market” (有效市场) are often paired together in government discussions related to China’s national development.

In DigiChina’s Forum on China’s 2021-2025 informatization plan, Paul Triolo wrote about on the significance of these two paired terms (see footnote 2), describing a section from the informatization plan calling for “integration of efficient markets and active government” as containing an “important formulation about the relationship between government and market that has been around for some time and is the subject of much academic debate in China.”

For an example of writing on this topic from Chinese state media, Economic Information Daily (a Xinhua-supervised outlet) published an article in October 2022 titled “Promoting the Building of an Integrated National Market Through Effective Markets and Active Government” (以有效市场和有为政府推动全国统一大市场建设). The article, which was shared via the Central People’s Government website, explained these phrases in the context of the policy recommendations on accelerating development of China’s integrated national market jointly published by the Central Committee and State Council in March of that year.