For more than two years, China's digital economy has faced shifting political and regulatory winds. The fintech giant Ant Financial was forced to halt its IPO as a state-market power balance played out. The dominant ride-hailing firm DiDi faced a long stay in the regulatory doghouse after its own IPO and an unprecedented cybersecurity review. The education technology market was decimated by regulatory shifts. And all actors had to adapt to the new Personal Information Protection Law and Data Security Law. Despite some efforts to reassure markets and a declared policy goal to unleash the potential of data as a factor of production, political risk and pandemic era challenges left the platform sector uneasy.

Since the beginning of 2023, some see a new beginning. DiDi is finally accepting new sign-ups. A top bank regulator said at least some tech platform rectification is "basically complete." Alibaba founder and Ant's political lightning rod Jack Ma is stepping away from his chairman role.

As 2023 and the Year of the Rabbit begin, is China's regulatory fervor in tech over, or is it the new normal? What has it wrought, and what's yet to come?

DigiChina posed these questions to our community of specialists in China's technology policy, and these are there answers. This Forum will be updated as further responses come in. –Ed.

ROGIER CREEMERS

Lecturer in Modern Chinese Studies, University of Leiden

Now that this interesting episode in Chinese technology regulation seems to be drawing to a close, what could we learn from it?

1: The regulatory offensive has often been called a “tech crackdown.” I, however, believe it is no such thing. It is not about “tech,” given that sectors ranging from robotics to corporate software, or semiconductors to biotech were nearly or completely unaffected. In fact, in 2021, the most intensive year of this campaign, venture capital investment into China’s tech industries reached record highs. It is also not a “crackdown” in the sense that Beijing wants to get rid of the platform economy. Quite the contrary: one policy document after another mentions the enormous importance of big tech to China’s development ambitions (although an exception could be made for the edtech sector, which was decimated by the obligation to go non-profit). Rather, regulators see the sector as so important that the excesses that had built up around it could no longer be tolerated. Moreover, the word “crackdown” seems to imply a temporary phenomenon, after which normality resumes. This is very clearly not the case: There is a permanent new approach to governing big tech. This will evolve, but will not be unwound. In my view, therefore, the word “rectification” is far more appropriate.

2: It is very attractive to ascribe the causes of this rectification to gossipy politicking, where Xi Jinping wanted to put Jack Ma back in his box, or the Party wanted more outright control over big tech companies. While that is not untrue, it is highly incomplete. If Jack Ma was the target, then why did companies like Tencent and DiDi suffer? And if the Party wants control over big tech, what does it want to use that control for? Instead, I believe the rectification, although partly inspired by political or bureaucratic considerations, also pursued multiple substantive policy goals, including managing macro-economic stability in fintech, combating market imbalances and anti-competitive behavior, responding to emerging social concerns, and limiting foreign influence on Chinese big tech. Moreover, the rectification also included interventions idiosyncratic to Chinese online governance, such as content control, which regulators would have made anyway. Overall, the clear message coming forth from this campaign is that Beijing wants these companies to be good corporate citizens that play a constructive role in the achievement of the Party’s development program.

3: The rectification provides a useful teachable moment for China analysts of every ilk. While it was often seen as a complete surprise to the companies involved, even a superficial look at related policy documents reveals many signals that something was coming. The drafting of the Personal Information Protection Law and Data Security Law started in 2018, the same year the E-Commerce Law came out. In 2019, the State Council published a comprehensive policy agenda for the “healthy and standardized” development of the platform economy, which outlined a significant number of the interventions that would come. The collapse of the P2P lending industry left investors—many of whom were ordinary individuals—out of pocket to the tune of 800 billion RMB and made financial regulators very jittery about other fintech business models. To be sure, the sheer intensity of the regulation might have been unanticipated. But anyone who claims they didn’t see it coming wasn’t looking.

JOHANNA COSTIGAN

Junior Fellow, Center for China Analysis, Asia Society Policy Institute

Just because China’s recent surge in tech sector regulations and its elevated efforts at content moderation coincided in time does not mean these two types of moves should be understood as part of a single master plan. Rather, they should be distinguished based on function—whether they meet the domestic political need to curtail freedom of expression, or address the international dilemma of crafting suitable regulations for emerging and rapidly changing technologies.

While often cast as part of the rectification—or crackdown, depending on your preferred term—China’s patriarchal censorship campaigns since 2020 are largely unrelated to Beijing’s pioneering, if possibly problematic, tech regulations. The latter are China’s unique response to the challenge, faced in every country, of creating fair internet regulation amid a fast-changing technological landscape. The former are manifestations of the CCP’ censorship pattern, which is idiosyncratic in both intention and capacity.

The “crackdown” on edtech, video games, and “sissy boys” says more about Xi-era political ideology, manifest online and offline, than they do about China’s tech-specific regulatory environment. Analytically categorizing such tight control over content as part of a unified tech crackdown along with, for example, regulating runaway algorithms and Party disciplinary investigations targeting beneficiaries of China’s semiconductor “Big Fund,” erroneously conflates Beijing’s responses to the global need for greater tech-related regulatory oversight and run of the mill, if advancing, Chinese digital censorship.

The content control story deserves independent analysis. Gaps in censorship implementation, evident for instance at the start of the November 2022 báizhǐ 白纸 (#A4) protests, show that while China’s content regulation is getting better and more ambitious, it remains far from perfect. That’s not for lack of effort. As China faces post zero-COVID case surges and overrun hospitals, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) on Tuesday announced it would “investigate and deal with fabrications about the trend of the epidemic and the latest prevention policies…to prevent the public from being misled and causing social panic.”

Punitive measures directed at the fintech industry on the basis of the “disorderly accumulation of capital” should not be grouped together with the proactive discourse-shaping actions taken by the CAC since 2020. The last couple years of Chinese politics have been largely guided by the enforcement and sudden abandonment of China’s zero-COVID policy and highly anticipated political events such as the CCP’s centennial and the initiation of Xi Jinping’s third term. These domestic developments heightened authorities’ incentive to ramp up positive online content—even if they had to play a role in creating it—and diminish creeping dissent before it gained significant traction.

PAUL TRIOLO

Senior Non-Resident Advisor, Center for Strategic and International Studies

China’s great technology rectification campaign is over! Long live technology rectification! Yes, major industrial departments and regulators have signaled over the past month that the great rectification effort targeting key players in the technology sector, primarily e-commerce, gaming, on-line education, and financial players is now more or less in abeyance. This is not surprising, and comes as Beijing is taking multiple measures to jumpstart an economy beset by three years of zero-Covid induced slowdowns and global economic pullbacks that have impacted China’s export sector. With tech entrepreneurs increasingly discouraged, Beijing also needed to give hope to the beleaguered tech sector overall that things would get better, and at least not worse. At Davos, outgoing economic czar and western stock market whisperer Vice Premier Liu He said “China is back” and dined with Western tech leaders and investors, a sign that both Silicon Valley and Wall Street believe things will get better, at least in the near term.

But there are other factors driving this regulatory pullback. First, some level of regulatory oversight is now baked into the system. Companies are on notice that Beijing will not tolerate certain types of behavior, especially if they go against the tenets of the somewhat nebulous concept of Common Prosperity. Executives get this. In addition, the other driving force behind the regulatory blitz that started after Jack Ma’s October 2020 Pudong speech is the need to focus on developing “hard” or “core” technologies. Companies also get this, and many of the big platform players like Alibaba and Baidu have stepped up investment in things like semiconductor design and AI. But things have changed significantly since the launch of the rectification campaign. Any hope of a major thaw in U.S.-China relations is now by the boards, and for Beijing it is now clear that the Biden administration will not relent on export controls targeting a growing range of tech sectors, including virtually everything that comes under the “hard” and “core” technology rubric.

Beijing now needs an all-hands-on-deck approach to investing and innovating fast in technologies most under pressure from U.S. controls, such as semiconductor manufacturing equipment, advanced GPUs, EV battery supply chains, AI, and quantum computing. With sectors such as e-commerce and gaming considered non-essential for national technology priorities, Beijing will turn more high-level attention toward figuring out how to revamp government support for the difficult technology sectors deemed critical. These are areas where Chinese firms are lagging well behind global peers, or where Chinese firms are doing well but may be impacted by U.S. export controls.

Over the course of 2023, we will see the unfolding of both what I call Semiconductor Policy 4.0 and Industrial Policy 5.0, as China moves beyond relying on concepts and frameworks such as the National IC Investment Fund, plagued by corruption and with an uncertain future, and Made in China 2025, which helped draw U.S. fire on trade and industrial policy and has clearly outlived its usefulness. Elements of the new approach to government support for tech are already evident in projects like New Infrastructure, the National Unified Computing Power Network (NUCPN), and public-private partnerships likely behind the efforts of Huawei and others to support the domestic advanced semiconductor tool sector and other key technologies such as AI and quantum computing. Looking forward, for 2023, less regulation of technology platforms and smarter government policies supporting core technologies will be the norm. In addition, for further regulatory moves and more government support, Beijing will almost certainly prefer many things be done in stealth mode, back to Deng Xiaoping’s hide-and-bide. China technology sector watchers will need to be extra vigilant.

TOM NUNLIST

Senior Analyst, Trivium China

The fundamental questions of big tech governance in China will remain unanswered. China’s so-called “tech crackdown” was not a monolithic event. Rather, it was a collection of disparate regulatory overhauls, grouped under a single (nebulous) theme: “disorderly expansion of capital,” a concept that appeared soon after the campaign began. In the past two years, the government endeavored both to fix specific industry-by-industry problems it identified, and also to address their perceived common underlying cause: the rapacious nature of capitalism. Results have been decidedly mixed.

In terms of specific problems, there are several examples of decisive change. Oversight of fintech, for instance, was placed solidly under the remit of banking regulators, eliminating a perceived “moral hazard” with strict new capital requirements that transformed the industry’s business model. The edtech sector was obliterated, with companies obliged to abandon core tutoring offerings and re-register as non-profits. More broadly, a decade-long M&A free-for-all was ended with tightened review rules and the closing of the notorious VIE loophole.

One might raise normative objections to these revisions, but they all proceeded from fairly firm logic and value statements by Beijing—X practice is negative for Y reasons—and resulted in unambiguous rules.

Many other tech crackdown outcomes are less clear-cut. Didi was fined over $1 billion USD for data security violations—although the cyberspace regulator (CAC)’s decision to forego a complete explanation, citing national security, raised more questions than answers. Ground-breaking algorithm regulations promised to open up a whole new regulatory arena, but how the government will effect supervision is a major uncertainty. China’s Anti-Monopoly Law was strengthened, but interpretation remains highly subjective, and the market regulator (SAMR) has signaled its intention to go easy on enforcement. It was never quite certain in any of these areas what precisely the government wanted, or was capable of, and continued confusion is no surprise.

Meanwhile, the overarching question of how to contain the “disorderly” impulses of capital remains entirely unresolved. Indeed, the issue has come full circle. Jack Ma unintentionally precipitated the crackdown by remarking that “[China] can’t use yesterday’s methods to regulate the future." But on January 3 of this year, the National People’s Congress invited a prominent professor to explain to lawmakers that traditional notions of “monopoly” are outdated and unsuited to contemporary regulatory challenges. The speaker argued that stifling platforms stunts the development of the digital economy, advised radically narrowing the notion of “disorderly expansion of capital,” and generally supported a lighter-touch approach.

While the views of a single person cannot be taken to represent the entire system, the fact that the speech was delivered suggests Beijing is scarcely closer to a governing consensus for big tech than it was in September 2020. On the contrary, it smacks of doubt that campaign-style rectification was a good idea in the first place, and certainly not something that ought to be continued.

What we’re left with is an expanded list of definitive “no-nos,” or the specific practices Beijing was already confidently against, and a set of emerging, but difficult-to-implement, regulatory regimes that need to be worked out more carefully. All of the above points to calmer seas in 2023.

LAUREN DUDLEY

Senior Analyst, Rhodium Group

Beijing is assuring platform companies that the worst of the regulatory crackdown is over, as leaders look to the digital economy to spur economic growth. But there will be no return to pre-crackdown business as usual.

Looking into 2023, regulators have promised to uphold the imperatives that drove the crackdown in the first place—such as anti-monopoly, data security, financial stability, and common prosperity—through more “normalized” supervision. Scrutiny might become less abrupt, with fewer record-breaking fines, unexpected investigations, and executives summoned to Beijing. But it will continue, especially as the state entrenches itself into some platform companies’ decision-making through “golden share” arrangements that may force companies to put government priorities over market-based calculations of competitiveness and profitability.

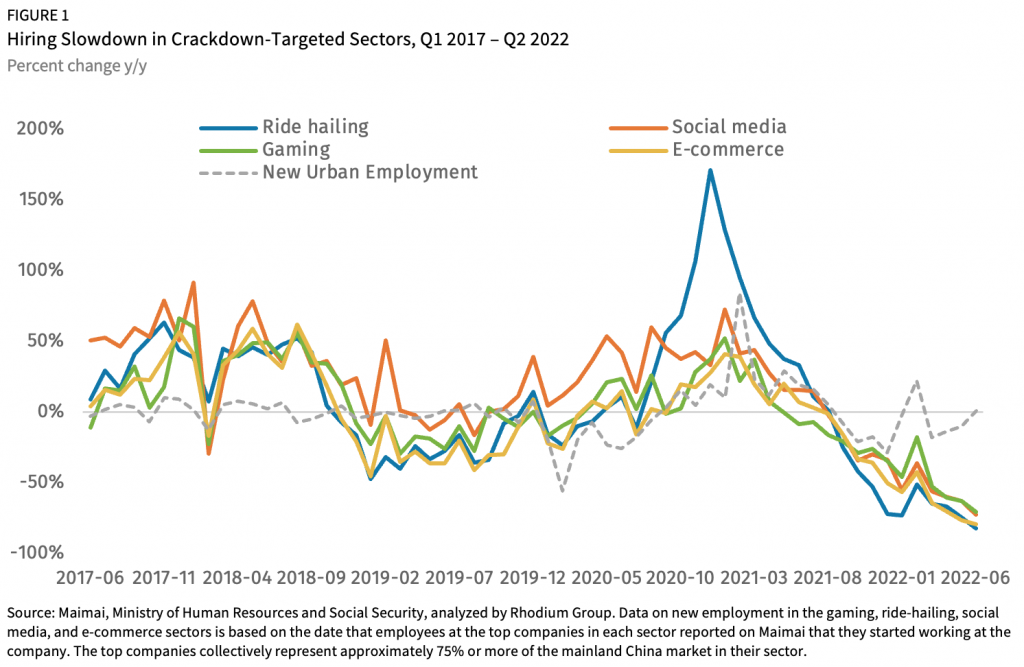

The true litmus test will be whether and how the platform sector rebounds in 2023. The past two years of the regulatory crackdown have cut deep into firms’ profitability and valuations, leading to a precipitous slowdown in new hiring. Data from Maimai shows that growth in new hiring at the top ride-hailing, e-commerce, gaming, and social media companies fell precipitously in the first year of the crackdown, down 50% year-over-year in December 2021, despite the boom in hiring in the global tech industry (Figure 1). New hires continued to fall into 2022, as did layoffs, with companies like Bilibili and ByteDance making fresh cuts in December amid global declines in the sector.

Will platform companies be confident enough to rapidly expand hiring or invest in new capabilities in 2023? Will business formation in the sector, which similarly fell during the height of the crackdown, outpace or at least equal that of the broader economy? Beijing surely hopes so. At the Central Economic Work Conference in December, policymakers pledged to support the sector so it can grow larger, hire more, and expand internationally as headwinds to economic growth mount.

But so long as Beijing intervenes in platform companies’ products and decision-making, these companies will perform below their potential. This puts pressure not just on the companies themselves, but on China’s broader economic outlook, given platform companies’ contributions to innovation, urban employment, and economic growth.

MEI DANOWSKI

Threat Intelligence and Geopolitical Researcher

Although DiDi and other platform businesses appear to have received the green light to operate, continuing rectification, regulation, and supervision of platform economy-related companies are most likely in the coming year, especially because the Chinese government considers the platform economy an important part of the “people-managed economy” 民营经济. The people-managed economy differs from the state-managed economy, i.e. state-owned enterprises. Although the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and government allow their citizens to run businesses, the Party expects “total surrender” from these businesses, requiring that they advance Chinese state goals. When businesses stray from the goals, the Party reins them in via rectification, regulation, and supervision.

“People-managed economy” is commonly translated in English as the private sector economy. However, Chinese private sector businesses are not the same as the private sector businesses in the West. The CCP often has the ultimate authority in business. The umbrella term “people-managed enterprises” covers two models: “state-owned, people-operated” 国有民营, and “private-owned, people-operated” 私有民营. Although the terms “people-managed economy” and “people-managed enterprises” 民营企业 are widely used in the government documents, “people-managed enterprise” is not an official type of business registration.

In May 2022, at a consultation meeting the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) hosted to discuss promoting the development of the digital economy, Chinese Vice-Premier Liu He emphasized supporting the sustainable and healthy development of the platform economy as part of the “people-managed economy.” This indicates the government views the platform economy as an important object of sponsorship and oversight.

In addition, even after declaring the rectification of issues at 14 large-scale platform enterprises as “basically complete,” the bank regulators proposed actions have suggested that more rectification and regulation are yet to come. According to Ma Jianyang, head of the financial market department of the People’s Bank of China, speaking at a State Council Information Office press conference explaining the 2022 financial statistics, the next step includes three actions:

- continue to speed up the rectification of the remaining few problems;

- enhance the level of normalized supervision, including further improvements to the regulatory system and mechanism, strengthened regulatory power over technology, support for platform companies to operate in compliance, prudent development of financial services, and zero tolerance for illegal financial activities; and

- research and develop financial support measures to promote the healthy development of the platform economy.

If the government takes these three actions, we can expect continuing rectification, increases in the government’s regulatory power, and directed financial support for the platform enterprises.

MARTIN CHORZEMPA

Senior Fellow, Peterson Institute for International Economics

Last week, headlines rang a false alarm that the “tech crackdown” in China was over. Guo Shuqing, who heads both the banking regulator and central bank’s Party committee, said the so-called “rectification” of big platform companies’ finance businesses (like Ant Group) was “basically complete.” Second, DiDi, China’s ride hailing leader, returned to app stores. Investigations into fintech super apps and DiDi are of particular symbolic importance because the tech “crackdown” narrative began with the suspension of Ant Group’s blockbuster fintech IPO in November 2020 and ramped up the following summer with the DiDi cybersecurity investigation that forced its disappearance from app stores. There are three reasons to keep the champagne corked.

First, Guo’s remarks only referred to the narrow subset of the government’s concerns on big tech: their financial business, which are under Guo’s jurisdiction. Most regulation on data protection, cybersecurity, competition, and consumer protection, fall under other departments like the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) and the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR). Despite the move on DiDi and leaks about concluding the investigation, they have not made similar announcements to signal policy shift.

Second, “basically complete” means “normalized supervision”—far from a return to the laissez-faire approach that reigned until 2021. Investigations are concluding, but they have caused a permanent shift in behavior and expectations. For example, before the planned IPO, Ant Group fully owned its highly profitable and rapidly expanding lending businesses. It hoped that much of its fintech empire would be considered “tech” and thus outside the net of financial supervision. The new normal is that Ant had to sell off 50% of its lending business to state companies to dilute its control and raise capital, and will own now only 35% of its credit scoring operations. Ties to Alibaba, including Jack Ma’s control of Ant, have been dismantled. Meanwhile, the entire firm is being placed under a tough financial holding company regime imposing a host of new requirements, in addition to tighter regulation of its individual businesses. This summary covers just some of the financial regulation, not to mention the host of new laws and regulations around data, competition, and cybersecurity that create new ongoing compliance requirements.

Finally, increased regulation is only the tip of the iceberg. The “golden shares” state entities increasingly are taking in nominally private firms give the state direct influence over firms, for example with seats on boards of directors and control over content strategy. In a sign of how far the pendulum to state control has swung, such shares were initially mooted in 2015 for the complete opposite purpose: to reduce government intervention, allowing “the State to relinquish its majority shareholding” in strategic sectors, e.g. partially privatize large state firms, without fully losing control.

While the period of huge regulatory waves crashing over China’s tech sector may be over, they now face a permanent rise in the level of regulation and state intervention.

KARMAN LUCERO

Fellow, Paul Tsai China Center, Yale Law School

China’s program of “tech rectification” has established a new normal for the Chinese tech sector. While the initial shock from a flurry of regulatory actions and heavy fines may have passed, regulators retain a swath of new powers and discretion, and the relationship that tech companies have with the government has shifted for good.

Despite being called a “crackdown,” the goal of the recent expansion of tech regulation was never to eliminate China’s tech sector, or even particular companies, so much as to force them into becoming better implementors of state policy. Big tech platforms also produce problems that many countries, not just China, are trying to grapple with. These problems cannot be solved overnight or by mere fiat. They require a regulatory infrastructure of laws and rules that can meaningfully influence the behavior of tech companies. This new regulatory infrastructure took years to build in China and is here to stay, both due to the apparent goal of increasing state control over tech companies and because new regulations expand the government’s regulatory powers and have permanently altered the environment in which tech companies operate.

First, the Party leadership wants to have more of a direct role in the development of the tech sector in China. Tsinghua University’s Liang Zheng describes how a series of laws and regulations, including the Cybersecurity Law, the Data Security Law, the Personal Information Protection Law, and the algorithm provisions are all aimed toward bringing “comprehensive management,” defined as using “legal, political, economic, education, cultural” and other means to “punish crimes,” “maintain social order,” and generally ensure “socialist modernization.” Lin Wei of the University of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences connects tech regulations with Xi Jinping’s goal of transforming China’s cyberspace into “spiritual garden“ without “pollution.” Some vaguely worded clauses, such as the algorithm provisions’ requirement that algorithmic recommendations “conform to mainstream value orientations” and promote “positive energy,” as well as leaked censorship directives, suggest that the CAC at least is invested in expanding its control over tech companies.

Other examples include state regulators taking “golden shares” in tech companies to influence decision making, and even the creation of state-owned platform services that will likely compete with private companies, such as a state-owned ride-hailing platform created for security reasons in the case of DiDi.

Second, the new laws and rules issues by the NPC, CAC, SAMR, the PBOC, and other regulators have built a regulatory infrastructure that greatly expands the power, discretion, and tools in agencies’ arsenals, including fines. Paired with occasionally vague rules and compliance requirements, these new laws and rules change the relationship that tech companies must have with government agencies as well as the culture of the regulatory environment in which they operate. Tech companies face many more risks and possibilities of punitive action. From this perspective, taking a more cautious approach and working more closely with the government presents an opportunity to better hedge against regulatory and political risk.

SEATON HUANG

Research Associate, Council on Foreign Relations

In the wake of suboptimal growth projections and the end of zero-COVID, state messaging has become increasingly supportive of platform enterprises as drivers of economic growth and innovation. Notably, during December’s Central Economic Work Conference, China vowed to employ policy mechanisms to bolster the private sector economy and entrepreneurship. More specifically, it expressed that platform companies would be supported for their efforts in “leading development, creating jobs, and showing their talents in international competition.”

But does Beijing’s embrace of platform companies taking a leading role in future economic growth spell the end of the so-called tech crackdown? Or were tech companies just casualties of the government’s desire to accomplish other policy objectives, suggesting regulation may continue?

Take, for instance, the video game industry, which until April 2022 had been subjected to an approval freeze by regulators. Beijing has long been concerned about online game addiction, instituting measures such as time limits and curfews to shield youth from what state media has called “spiritual opium.” But as China begins to reopen its economy, it has also publicly recognized the gaming industry’s “extremely high economic, technological, cultural, and even strategic value.” Conveniently, recent increases in game approvals arrived just as the country declared victory in its campaign against teenage video game addiction.

Next, let’s turn to Ant Group. While other platform companies such as DiDi and Meituan have been punished for unfair competition, Ant’s rectification was seen as necessary due to the risk that it would overtake functions of traditional state-led financial and banking institutions. China’s concern with Ant’s ability to provide consumer debt-enabled financial products at a large scale echoes its shutdown of P2P lending. Ant’s status as the preferred digital payments platform may have also been seen as a challenge to the initial launch of the centralized digital currency, e-CNY, though it seems Beijing has come around to leveraging Ant’s market share for increased cooperation in this space.

So, what does Guo Shuqing’s declaration that platform rectification was “basically complete” and would be followed by “normalized supervision” really mean? Remarks made by another central bank official clarifying that the campaign was mostly directed at “business operations, regulatory arbitrage, disorderly expansion, and infringement of consumer rights” suggest that while the antitrust chapter of the “crackdown” has been effectively resolved, the government remains willing to use regulatory instruments to accomplish its other objectives or assert its authority over certain sectors.

As China turns back to platform companies in the hopes of sparking economic growth in 2023, firms will want to know whether “normalized supervision” entails the possibility of being blindsided by sudden changes in the regulatory environment. Although Beijing will likely promise no such thing, it will need to deploy more deliberate policy measures to inject confidence into platform economy actors. Public reconciliation with some of the former executives that left their positions amidst the regulatory blitz may be a step to rebuild trust between the government, tech companies, and their investors.